Among the most vulnerable links in a power network are points of interaction between live equipment and wildlife such as birds and scavenging carnivores. Taken together, these creatures present a constant threat to the safe operation of assets. Indeed, the global economy is said to suffer great losses each year due to sudden power disruptions and up to 12 percent of these are estimated to be due to wildlife intrusion. If outages classified as ‘source unknown’ are factored in, the impact is greater still since many of these also link to wildlife. Moreover, this risk is only growing given the focus on lowering costs, saving space and making electrical infrastructure less visible through compaction – in the process reducing distances that need to be breached to create faults.

This past INMR article discussed how a utility in Western Canada responded to this threat by retrofitting vulnerable substations with protective covers and other wildlife deterrents.

A number of factors have been driving growing interest in applying wildlife protective devices at vulnerable substations. One, of course, is the universal goal of maintaining high system reliability. Another relates to the consequences of animal interaction with energized structures, which are not just power interruptions but also damage to expensive assets. Industry sources claim that such risk at substations could be reduced by 80 per cent through selective application of well-designed wildlife protection products.

Yet another factor behind the interest in wildlife mitigation products relates to the potential for fines should protected species be electrocuted during phase-to-phase or phase-to-ground contacts. Raptors, for example, typically have wingspans that place them at elevated risk of being in contact with energized equipment. This can become a problem at substations where clearances are determined by required flashover performance and not by the wingspans of local birds.

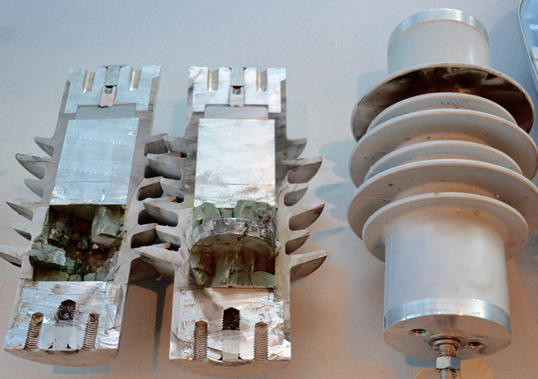

Wildlife protection devices being offered have different designs and are made from a variety of polymeric materials. One of the keys to good performance is fit. Since power arcs travel through air, the gap between creature and live fitting is critical. Any crack or seam in a protective covering could allow the arc through and the higher the voltage the greater this risk. Wildlife behavior also requires good fit for best results. For example, bird nesting at substations attracts cats, snakes and other predators that can dislodge loose-fitting covers as they push to the nest. They get electrocuted and the result is a costly outage.

Materials themselves are also important. All animal protection products start with a problem that must be addressed. But users need to be certain that whatever is being applied does not cause more problems than it resolves. For example, materials used must be fire-resistant and one of the goals behind past IEEE guidelines for their application was to assure that wildlife protection devices do not themselves create problems over the long-term.

One of the considerations when it comes to composition of materials used in these products is suitability to an outdoor environment of electric field and persistent high UV. Materials must be inert and resistant to tracking and erosion since they will face the same stresses as insulators, including dry band formation that can leave carbonized dots on their surface. Users are therefore advised to look at the tracking and erosion performance as well as UV test data for any wildlife protection device they consider installing. This is the only way to be sure these products will survive for years in a potentially hostile service environment. It is also essential to ensure that whatever latches attach devices to the equipment they protect must not deteriorate. If that happens, the devices can break off or shift under wind, exposing the live ends of equipment to contact by wildlife.

Wildlife cover on protected arrester in Thailand no longer fits properly.

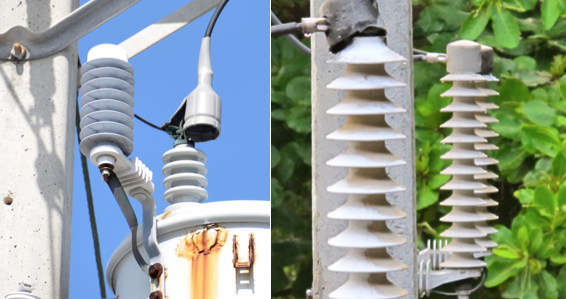

In the past, wildlife protection devices were often made from inexpensive PVC or EPDM. But more recent years have seen more robust polymers such as EVA, silicone rubber or blends of polyurea that are better suited for power industry applications. These are offered as extruded sheets that can be cut in templates to fit whatever equipment is being protected or pre-molded in the factory to specific shapes.

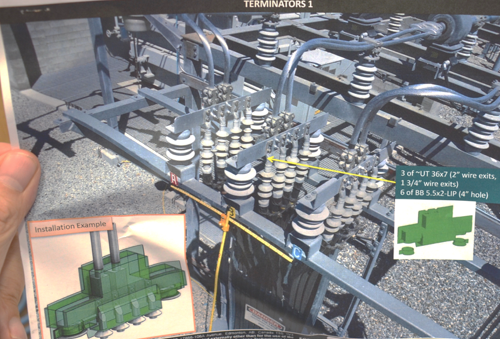

Apart from material, which has to be durable enough to last at least 10 to 20 years in the case of a substation, another key element of wildlife protection devices is speed and effectiveness of application. The former is especially important if scheduling an outage is needed to install them. For example, designing protective devices for custom fit not only maximizes performance but can also translate into lower installation times.

Hotsticks have been developed that allow wildlife protection covers to be put up with the equipment energized. Indeed, the difficulty in scheduling an outage has been one of the reasons why many substations remain unprotected against wildlife intrusion. The clear trend is therefore toward wildlife protection devices that can be installed without de-energizing the equipment. Suppliers of wildlife protection devices must ideally co-operate with the customer to develop a ‘site protection plan’ to identify potential problem areas and customize the solution in each case.

Another trend in this business is growing sales of wildlife protection devices directly to manufacturers of transformers, arresters, re-closers, etc., so that such equipment is already equipped with these at time of purchase. End users should always take care, however, since factory-installed caps can sometimes be sourced from companies with little experience in wildlife protection and may be made of materials that will not stand up many years in a demanding service environment. Utilities may therefore wish to work with their OEM suppliers of such equipment to specify exactly what they will need when it comes to factory-installed wildlife protective devices.

Those in the wildlife protection business claim that there are few if any alternative solutions to covering up equipment where clearances are most at risk. Instead, the real alternatives to improved wildlife protection of equipment rely on restoration schemes and relays or reconfiguring structures to achieve extra spacing between phases and phase-to-ground – solutions that can prove costly and take time. The consensus is therefore that reducing the problem of wildlife interaction with power infrastructure can most practically be accomplished by covering exposed equipment at substations with specialized protection products.

Case Study: Protecting Substations Against Wildlife Intrusion

Glenmore and Recreation Substations in Kelowna, British Columbia offer example of substations that have encountered wildlife problems over the years. Glenmore, built decades ago, is bordered on one side by a busy thoroughfare with lots of traffic, making it seem an unlikely candidate for such issues. Yet its rear faces a forested mountain ridge and trail where there are populations of squirrels and other rodents. This in turn has attracted large birds of prey with wingspans that easily bridge clearances.

In 2008 and again in 2012 and 2013, for example, contact by squirrels with energized bushings caused serious damage to breakers. Apart from this, birds were found electrocuted alongside potential transformers (PTs). While smaller than local raptors, they nevertheless had wingspans long enough to bridge the clearances of this equipment.

Engineers at the affected utility have identified Glenmore and Recreation Substations as examples of facilities that could benefit from greater installation of protective wildlife covers. These facilities have also been selected for evaluation of other solutions to mitigate impact of wildlife intrusion, such as protecting conductors and live fittings as much as possible to reduce risk of phase-to-ground or phase-to-phase faults. They have also studied the possible role of devices intended to discourage creatures from even entering.

Each station was equipped with special ultrasonic noise emitters to frighten small animals. Since rodents such as mice and squirrels hear at a frequency above 20 kHz, the noise emitted is inaudible to the human ear. Two different options have been studied – an indoor version intended to keep mice and rats from establishing nests in control rooms and enclosed equipment and outdoor versions meant to keep squirrels and other small animals from approaching equipment such as transformers.