There is a general assumption that high price is always good for the seller while low price is always good for the buyer. In the world of electrical insulators, however, this does not necessarily hold true. The acquisition cost of an insulator is in fact far less important than is the performance and service life it will offer. If a higher price better predicts satisfactory long-term performance, this is good for both seller and buyer.

Warren Buffet once remarked, “price is what you pay for something; value is what you get”. In the case of insulators, acquisition cost is a relatively small component of total lifetime cost, which can prove to be many times higher. The real value of an insulator lies in how well downstream life cycle costs can be controlled within acceptable limits.

An insulator is a strategic component governing the performance of a very expensive asset. While insulators typically account for no more than 5 to 10 percent of total project cost for an overhead line or substation, problems with insulators are usually the leading cause of unplanned outages. Moreover, because of their high number and strategic importance, they are also a component carrying high inspection and possibly very heavy maintenance costs.

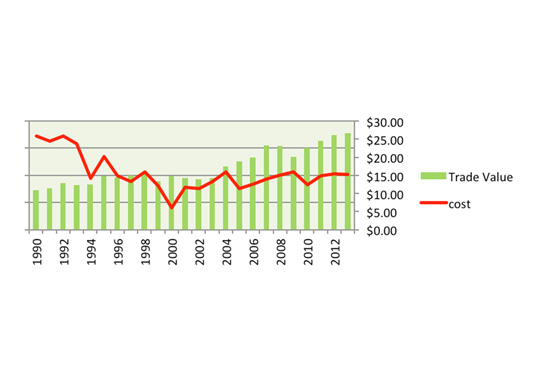

Given the above, it is worth examining what has happened to the price and quality of insulators starting around 1990.

In his 1988 book, ‘INSULATORS FOR HIGH VOLTAGES’, John Looms of the United Kingdom’s CEGB (precursor to the National Grid) compared prices of insulators at the time with prices decades earlier. He discovered that these had barely changed in numerical terms on an equivalent weight basis, in spite of inflation, and concluded that insulators had become too ‘cheap’, especially if one considered their important role in power transmission and distribution.

But even more changes were soon on the way.

The 1990s marked the start of dramatic facelift for the electrical power supply industry in general and for the insulator industry in particular. Firstly, as utilities became privatized and deregulated to create more competition, past long-term relationships between power utilities and local insulator manufacturers began to disolve. Suddenly, utilities were no longer willing to support local suppliers if this meant paying a higher price. Adding to the increased competitive pressure was the fact that large OEM customers began to establish global supply chains to acquire insulators from the most economically advantageous sources across the globe.

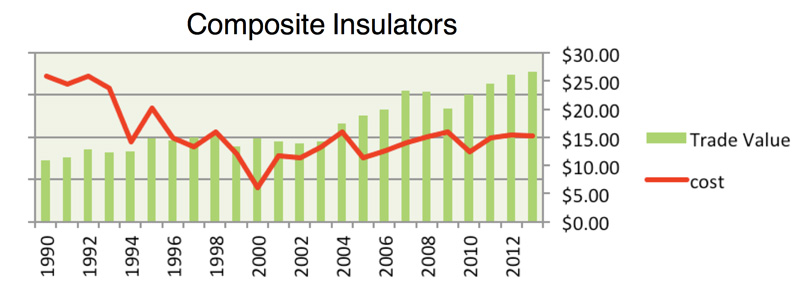

Finally, growing acceptance of composite insulator technology starting in the mid to late 1990s created new cost structures for the industry that allowed prices to be driven even lower. These insulators could be produced more quickly and with less labor content than porcelain or glass equivalents. The number of competitors also grew substantially since it was much easier for new suppliers to enter the composite insulator segment than to build new porcelain or toughened glass insulator plants.

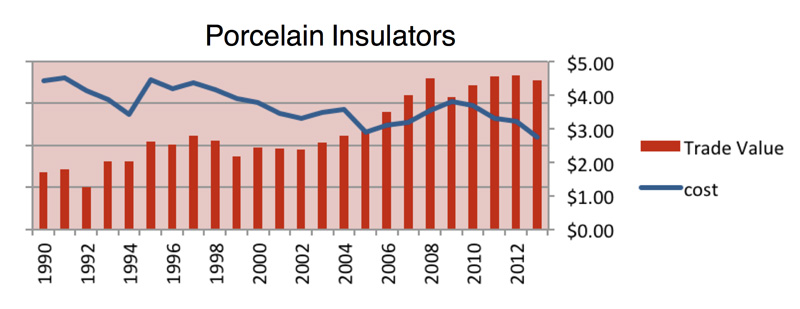

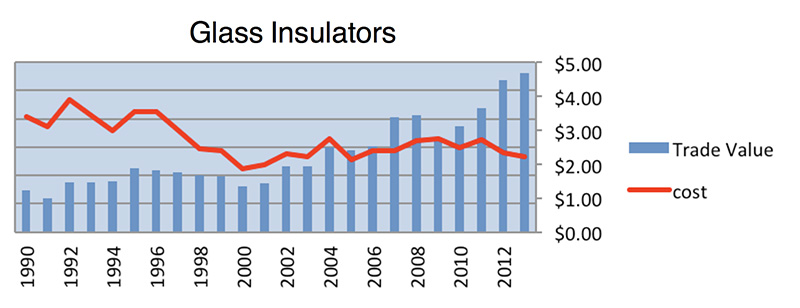

Together, all these developments put unprecedented pressure on price of insulators. As shown in Figs. 1, 2 & 3 from a past study of international trade in insulators by Goulden Reports, 1990 marked the start of years of price erosion for glass, porcelain and composite insulators, measured in export value per kg.

While this past trend might sound like good news for insulator buyers, it did come with certain potential risks. Insulators, like other components in a power network, are expected to function reliably for decades. Unreasonably low prices may lower acquisition costs for grid operators but can impose high costs down the road, especially if insulator suppliers have to ratchet quality downward just to survive.

By 2010, Prof. Liang Xidong of Tsinghua University in China – now Convenor of an IEC Working Group on updating insulator standards – sounded the alarm about what would happen if price levels of insulators continued to decline. He noted, for example, that the price of silicone insulators in China for application on 110 to 500 kV systems at the time had become much lower than at the start of their use many years earlier. While economies of scale in manufacturing had helped drive down costs, the real factor behind this price decline was intense competition between the new and the more established manufacturers.

Prof. Liang saw a clear danger. With falling price levels, manufacturers would have to find ways to cut costs by optimizing materials and possibly lowering the resilience of their insulator designs. Now, the goal became not producing an insulator that offered many years of trouble-free service but rather one that would be less costly to manufacture yet still pass all tests required in the standards.

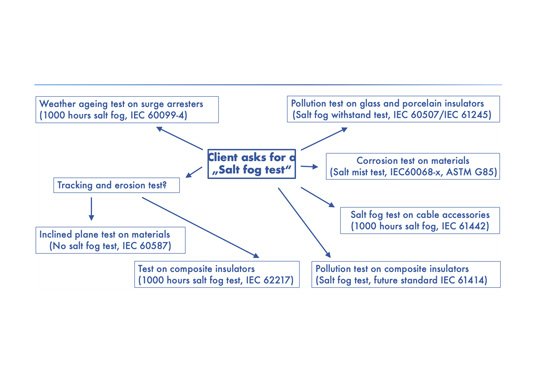

By around 2015, utilities in Europe and elsewhere began to detect irregularities in some insulators in their inventories. There were also increased cases of failures being reported from the field. Based on this, test laboratories soon began to receive more and more requests for non-standardized tests based on specific user requirements. As reported in 2019 by experts at a major test laboratory in Sweden, the utility industry began to feel that several existing IEC standards needed to be revised and adapted to more stringent conditions since related tests were no longer seen as sufficient to ‘weed out’ inferior quality. The different types of failure mechanisms experienced in service only underlined the need for tougher test requirements such as increased duration, increased number of samples and possibly entirely new test methods altogether.

The question therefore arises: how best to keep a proper balance between price and quality?

This question is central to reliable and efficient operation of all power systems. But to answer this question one must first distinguish between high quality and poor quality insulators. For example, what constitutes good quality in a composite insulator?

According to Professor Liang, “quality should be judged by insulator performance over long-term operation on the network – something that is not easy to assess in advance at the time an insulator is manufactured and purchased by the customer. Rather, this can be judged best by the results of testing. If an insulator passes the test, it is typically a qualified product.

But, as discussed, it is no longer always possible to predict an insulator’s long-term performance before it is put into operation by relying only on present standards. And it is especially difficult to distinguish a truly high quality silicone insulator from one that only passes required tests.

Prof. Liang noted that to assess expected long-term performance, utilities in China adopted different requirements. Some, for example, felt a composite insulator was of sufficient quality if it could perform reliably for 10 years. These utilities then decided to replace all old composite insulators with new ones – even if they still appeared in good condition. Apparently, the utilities felt that 10 years with almost no maintenance was good enough and already much better than the porcelain insulators used before, which had required frequent manual cleaning. They simply did not want to take the risk that new composite insulators might fail after more than 10 years in service. Other utilities in China insisted that a good quality silicone rubber insulator should be safe in operation for 20 to 30 years. Hardly any looked to such life spans as 40 or 50 years. Of course, these different life expectancy requirements had great influence on acquisition costs and suitable test standards.

Users and manufacturers have the same goal when signing a sales contract, namely to equip a new line or substation with insulators that will perform without problem for many years. But there are challenges to this historic paradigm as more and more suppliers have found themselves competing on price rather than on quality. Said one industry insider, “the pressure to survive is high.” What he was really saying is that unreasonably low price levels may force certain suppliers to take ‘shortcuts’ just to stay in business.

The important message: end users must always take a long-term view whenever buying a component that is as strategic to the safe and reliable operation of a power network as is the insulator. That means price alone should never be the basis for choosing one supplier over another.

While generally regarded as a commodity with comparatively little technology content, the reality is that electrical insulators can prove the fatal weakness of any power system. Poorly performing insulators will doom even the best-built lines and substations to problems and invariably lead to frequent outages or high maintenance costs – or both. This is an undeniable fact that elevates the strategic importance of the insulator to a level far in excess of its relatively minor share of total investment cost.

It is a question of which principle is the more important: ‘short-term gain but with possible long-term pain or short-term pain for long-term gain’.