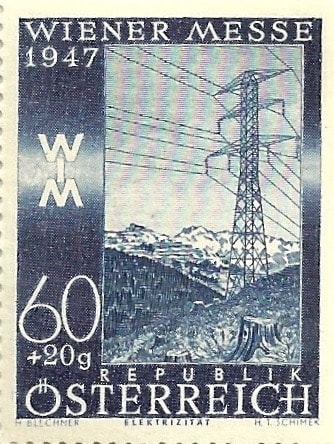

2021 marks the 130th anniversary of the first-ever overhead line – a three-phase AC line put into operation in summer 1891 and running from Laufen to Frankfurt. Back then, losses ran at about 25% but this achievement was nonetheless regarded a true technological marvel. Within 50 years, country after country across the globe began to link growing availability of electricity with economic and social progress. Overhead lines were universally praised – even memorialized on postage stamps.

These days, few people collect stamps. And, sadly, fewer still look at overhead lines with the pride and admiration of the past.

So what happened?

There are several explanations for today’s public distrust and near universal opposition to overhead lines. One is that, in spite of definitive evidence to the contrary, these have been linked to unseen health risks. People are frightened by dangers they cannot see and therefore easier to convince that electromagnetic fields are somehow harming them. All this started in the late 1970s with a study carried out in Denver, Colorado that examined environmental factors around the homes of children stricken with cancer. The magnetic field produced by current flowing through residential wiring was estimated at about 0.2 μT and it was suggested that this might be a cause for the association. The design of the original study was exploratory in nature but nonetheless given consideration by governments, academia and industry and spawned vast international research. Practically all studies found that an association between proximity of power lines and incidence of childhood leukemia could almost certainly not be attributed to magnetic fields being generated. Indeed, some research focused on lines workers exposed to average fields up to 20 times – and even as high as 1000 times for short time spans – typical residential levels. Those studies failed to demonstrate any increased cancer risk. In fact, results showed cancer mortality rates 20 to 30 percent lower among these workers versus the general public – an observation that came to be known as the ‘healthy worker effect’.

Several experimental studies were later carried out on volunteers at field levels of from 100 to 3000 μT. Subjects were unable to perceive the presence of these high fields and there were no adverse health effects or signs of toxicity. The absence of toxicity at levels up to 50,000 times the average field found in homes (i.e. 0.1 μT) confirmed that any carcinogenic effect is unlikely. Incidentally, notwithstanding such findings, the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection recommended, as a precaution, that maximum exposure limit for the public be set at 200 μT and 1000 μT in the case of power industry workers. Today, most experts believe that the hypothesis raised by the Denver study was a false alarm and the volume of data over the past 40+ years confirms that fields below the above-recommended power-frequency magnetic fields are too weak to influence human biology.

Apart from perceived health risks, another reason the public has fallen out of love with overhead lines is what is increasingly seen as the blighting of urban and rural landscapes by unsightly transmission towers. And here, one must accept that this perception has often proven an unfortunate reality. Oftentimes, magnificent landscapes and scenery are blighted by oversize transmission structures that sometimes ‘hide the sky’.

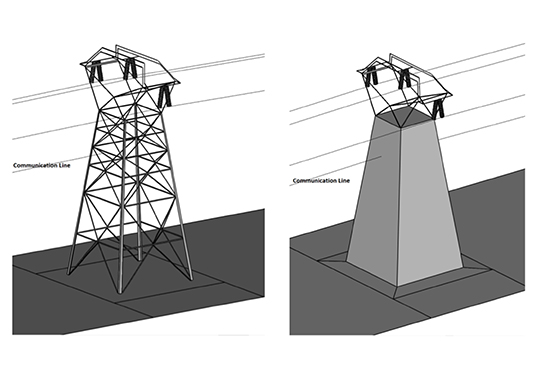

One country that has been at the forefront of halting construction of new overhead lines based on tower designs of the past has been Denmark – the first place to ban new lattice structures at transmission voltages. Designers and engineers there came to the conclusion that continuing to build these types of towers suggests lack of progress in power transmission and gives the mistaken impression it has lagged behind other industrial sectors.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

It is clear that overhead lines suffer from an image problem – in spite of all the benefits linked to the electricity they help deliver. No new stamps have been issued to praise them for decades.

Given this, the 2015 INMR WORLD CONGRESS in Munich, devoted a session to reviewing proposals for how structures of the future might look. There, expert after expert agreed that power lines have contributed to their present image problem by remaining mostly unchanged in appearance. Indeed, it is hard to think of anything that has not changed dramatically over the past 60 years – from cars to trains to boats to buildings to telephones to fashion. But many if not most power lines built these days still resemble what one finds on stamps from the 1940s and 50s. Just look at the Austrian stamp from 1947, which depicts a structure much like what is still being used for new lines built in recent years.

Of course, the primary goal has always been to deliver power reliably and affordably on a system that will last decades. Without these criteria being met, little else matters. But this is an age where appearance influences how things are perceived. If something looks old and outdated, it is easy to oppose, fear and perhaps even to despise.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

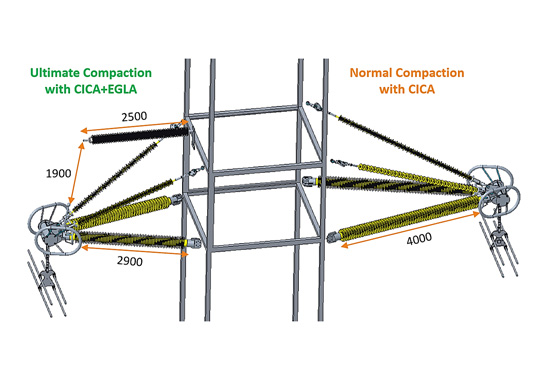

The good news is that the electricity supply industry has come to the realization that overhead lines of the future can no longer be built by relying solely on designs of the past – no matter how successful these have proven. Among the challenges facing overhead lines over the next 130 years will be to deliver much more power, mainly from clean renewables, along existing corridors and using compact, highly aesthetic towers. What society could find reason to complain about that?

CLICK TO ENLARGE

It is time to reconfirm our love affair with overhead lines because, these days, only three things are still certain: Death, taxes and overhead lines.

Contributed to INMR in 2016 by Marvin Zimmerman & Dr. Konstantin Papailiou (former Chair, CIGRE SC B2 Overhead Lines)