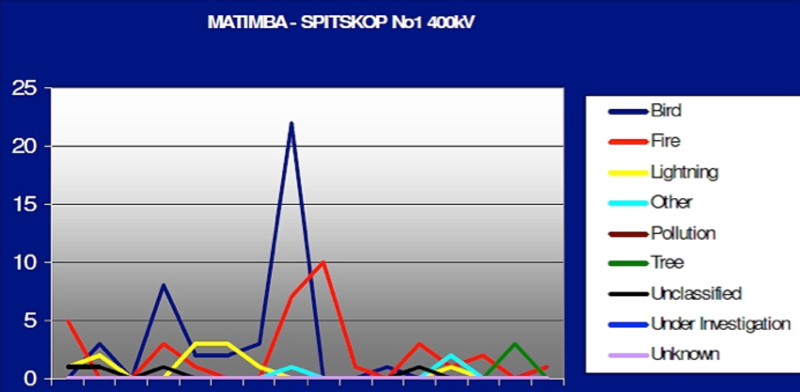

As industrial contamination sources come under greater and greater scrutiny, flashover outages attributed to birds – often included under the category of ‘unexplained outages’ – seem to be playing a proportionately greater role. This edited past contribution to INMR by Igor Gutman in Sweden, Evgeny Solomonik in Russia and Wallace Vosloo in South Africa examined how birds and power lines co-exist in what is a close but mutually threatening relationship.

Past service experience from countries such as Germany and Russia has suggested that as much as to 70-80% of all outages on overhead lines can be directly attributed to birds. Even though these types of outages are characterized by successful automatic re-closure from 94 to 97% of the time, power utilities are still concerned. In older days, the concern was due mainly to old oil circuit breakers that required maintenance after each cycle of about 15 operations. More recently, the worry has been due more to requirements for power quality and availability since utilities set their own internal rules on average outages permitted each year per 100 km of line.

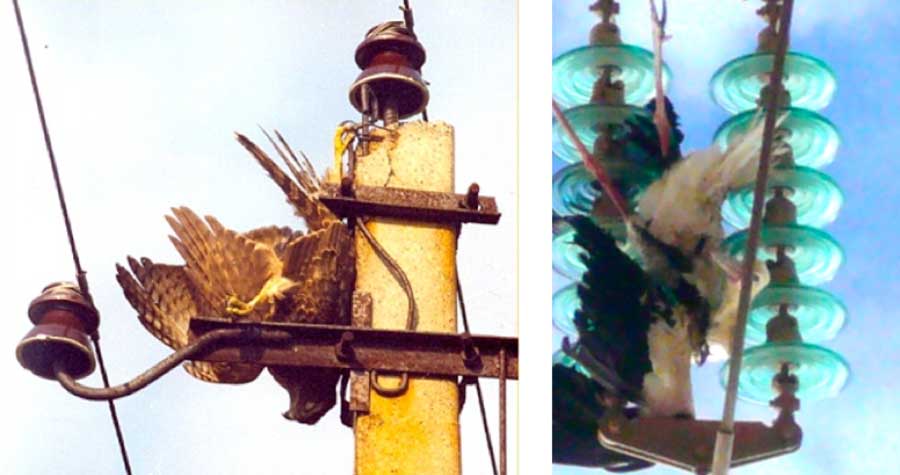

In any discussion on problems of birds and power lines, it is important to distinguish the situation for distribution voltages from that in the case of transmission. The two are vastly different problems requiring much different solutions. In the case of distribution systems, the central problem is electrocution of birds. Estimates of the numbers of birds killed each year are shocking. For example, one source reported that 7 million die annually only in the European part of Russia. Another reference estimated a density of electrocuted birds at about 15 for every 10 km of line. Especially dangerous in this regard are those lines with vertically installed pin-type insulators because the conductor sits on the insulator, not below as in a suspension string.

What makes this situation the more tragic is that the threat posed to birds by distribution lines has been documented for years. Moreover, there is adequate knowledge on how to solve or least largely reduce the problem by insulating the conductors close to the tower using protective devices (e.g. insulating covers) of different shape and design.

The principal requirement for such polymeric devices is that they have a service life similar to that of the components they are intended to protect, e.g. conductors, insulators, arresters, etc. In this regard, they must be resistant to deterioration from weathering and UV. Experience with such devices has generally been positive and the only issue is the cost necessary to provide sufficient protection in areas known to have high concentrations of birds.

Unlike the widespread carnage affecting birds along distribution lines, transmission networks face a challenge of a different sort. Here, flashovers of suspension strings by streamer-type excretions are relatively common and affect lines up to 500 kV. In these cases, birds fly away basically unharmed, though stressed by the effects of the flashover, while network equipment has to be relied on to quickly restore the line.

Problem Overview

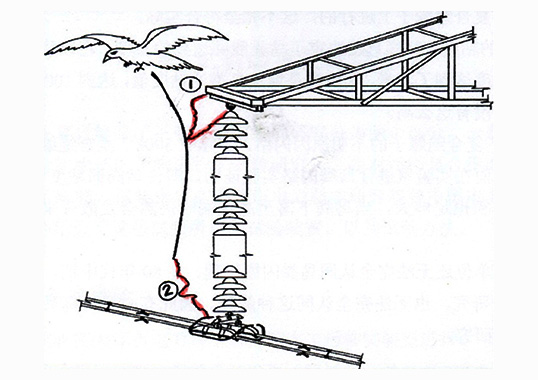

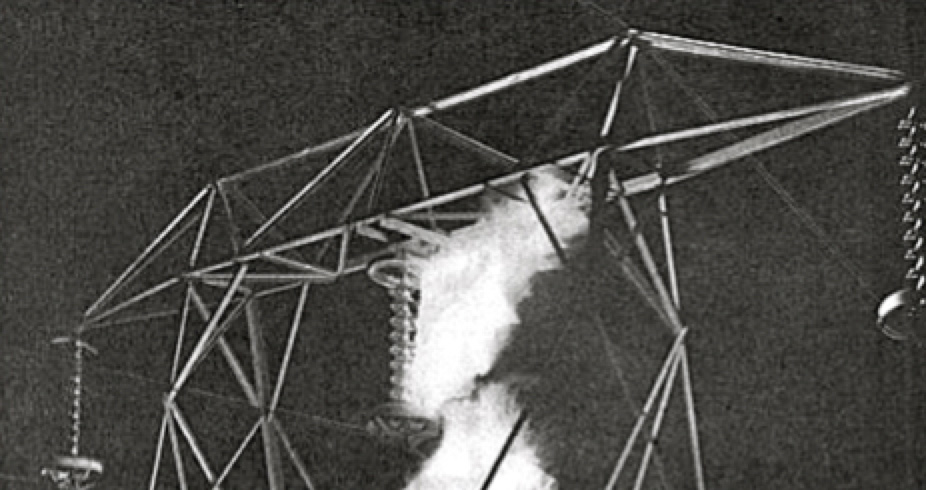

The problem of outages on overhead transmission lines due to streamer-type flashovers is caused by typical bird behavior after perching on a tower cross-arm. Before taking-off, they usually empty their bowels and release up to 60 cm3 of excrement mixed with conductive urine at one time and coming out at some pressure. This creates a conductive path that bridges the air gap between tower structure and conductors resulting in a flashover either in parallel to or a little apart from the insulator string

Detailed investigations of these streamers have been made using high-speed cameras in HV laboratories where researchers sometimes even chained birds to mock-up towers. This research confirmed that the continuous part of the streamer attain lengths up to 2 m and move at speeds of 2 to 5 m/s. The angle of a streamer to the cross-arm can be as high as 60-70° yet still lead to flashover. Resistivity of dried excrement has been found to vary from 800-2000 Ω∙cm. In its natural state, this will vary slightly by species, e.g. storks (220-610 Ω∙cm); eagles (190-770 Ω∙cm); and chickens which serve as reference (260-850 Ω∙cm). It should be taken into account, of course, that the average body temperature of a bird is 41.5°C and that actual resistivity will be less at lower ambient temperatures.

Experiments confirm that, given these parameters, it becomes possible to flashover insulator strings up to 500 kV AC and ± 400 kV DC. In Russia, for example, research showed that flashover occurs at a resistivity of about 600 Ω∙cm (using excrement collected at a zoo) and a dielectric strength of 70 kV/m, which is less than the maximum operating voltage for the 110 kV insulators tested. Similarly, in the U.S. it was found that, at a resistivity of about 120 Ω∙cm (from samples of excrement mixed with raw eggs and salt), a 500 kV suspension cap & pin string flashed over at 320 kV – about 1.1 times nominal operating voltage. It is worth noting that during these experiments the streamer could be as far as 70 cm from the string yet still affect it. A bird excretion flashover simulator was developed in South Africa and experiments performed at a resistivity of about 70 Ω∙cm. This figure was selected after analysis of samples from two species of eagle and the mixture consisted of cellulose, salt and tap water. The results were then used to investigate the physics behind bird streamer flashover.

It certainly seems clear that, from an engineering perspective, the problem of bird streamer flashover on transmission lines has been confirmed and documented. The issue then is how best to protect a line from birds perching in the vicinity of insulator strings and periodically flashing them over. This requires asking: why are birds even there at all?

Bird Streamer Flashover

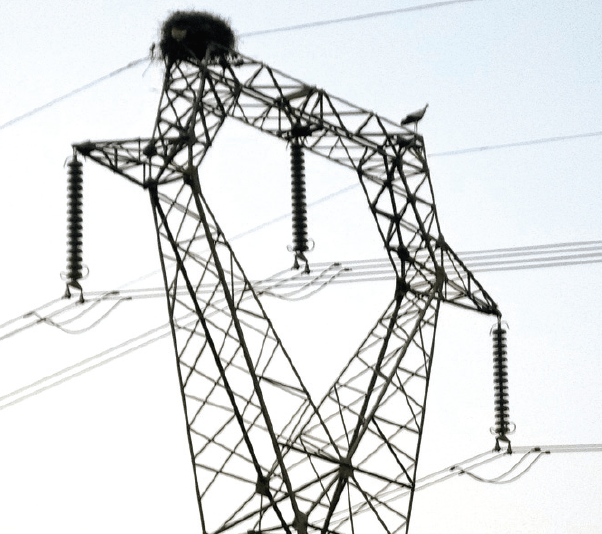

According to ornithologists, there is an obvious reason why transmission towers attract large raptor type species such as owls, vultures, eagles – the usual culprits causing streamer type outages. The structures provide them with ideal platforms for hunting, roosting and nesting. Indeed, the cross-arms of a typical 110 kV tower are located at the optimal height for buzzards to hunt prey along the right-of-way.

Moreover, once birds establish a roosting site, they continue to use it year after year. In Finland, for example, two lines of identical design and sharing the same corridor but constructed at different times had much different operating histories. The older line suffered from unknown outages while the newer one did not. The reason was that the first line was already occupied by most of the large local birds, which then never moved over to the second line. A similar example from South Africa showed that only half a line suffered from unknown type outages while the other half did not. In this case, the reason was that the problematic half was under control of eagles that settled near its end, while no other raptors watched over the other half.

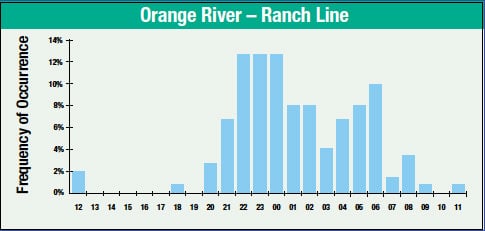

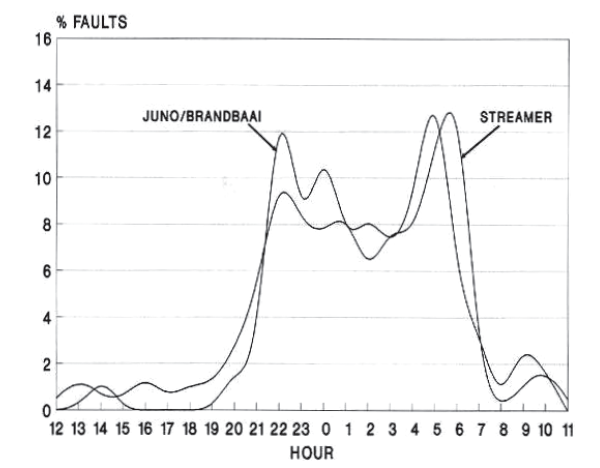

This demonstrates that it can prove worthwhile to study the behavior of birds occupying any portion of a transmission line. In most cases, birds come to rest and sleep towards dusk and take their place on the cross-arm or in the nest. Sometimes, they empty their bowels for the first time right after landing, thereby providing the first peak of outages around 10 to 11 PM. The birds then empty their bowels a second time in the early morning (4 to 6 AM), most probably to reduce body weight before takeoff. They fly away, leaving behind yet another potential outage to be dealt with.

In summary, transmission towers offer a natural place for birds to rest and hunt. The only issues left to resolve are: How to be certain that the flashovers are indeed bird-induced and, if so, what can be done about it?

Clues for Utility Maintenance Personnel

As discussed, the peak number of unexplained outages (probably from bird-induced flashovers) take place in the early morning. This normally occurs in clean or slightly polluted areas during conditions of high humidity, as insulators are wetted by morning dew. Thus, it is not always easy to pinpoint the exact cause of the flashover. For example, it could well be a classical pollution flashover or one related to a problem with E-field.

Recommendations to ascertain whether or not birds are involved in an outage include:

1. Inspect the problematic line by helicopter, checking for traces of bird contamination on surfaces of insulators or on cross-arms. Nests can also be observed on particular towers;

2. Contact local ornithologists for any maps that show density of different species in the area. Students can be of great help in the field to observe bird activity near an affected line;

3. Establish presence of any nearby agricultural land, fish farms or sugarcane fields;

4. Check seasonal pattern of outages and relate this with natural departure/arrival of migratory birds and time of birth of their juveniles. In the European part of Russia, for example, there is typically a sharp increase in outages during August, related mostly to juveniles being taught how to fly and feed;

5. Check daily pattern of outages and relate this with typical morning peaks;

6. Verify percentage of successful auto re-closures (typically around 95% if birds are involved);

7. Monitor the area below the line for dead birds or burnt feathers;

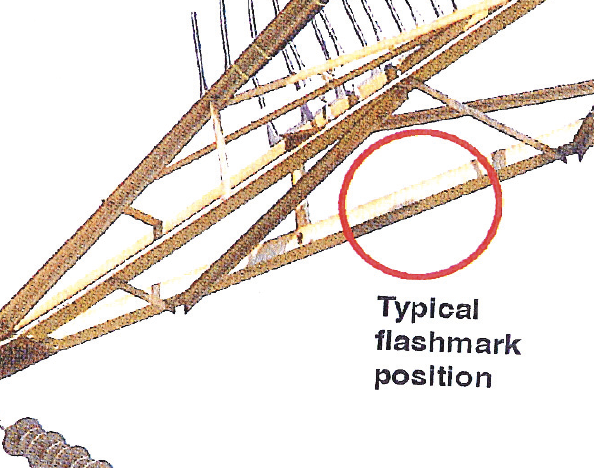

8. Check the appearance of flashed insulator strings. In the case of bird-induced outages, there are usually traces of the arc root on the conductor (at 1 to 1.5 m from the insulator), on the cross-arm above the insulator or at the top one or two cap & pin insulators.

Solving Problem in ‘Bird Friendly’ Ways

Guidelines/standards exist with recommendations in these situations, including the IEEE Guide for Reducing Bird-Related Outages, Eskom Transmission Bird Perch Guidelines, Russian Regulations on Design and Reconstruction of Electrical Installations (for lines and substations). Still, engineering bodies continue to come under pressure by environmental groups. For example, the IEEE Guide notes “Disturbed by the continuing large numbers of birds electrocuted and colliding with power lines, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began to step up enforcement of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. All migratory birds are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In one landmark case, a utility was sentenced to three years probation for electrocuting 17 eagles and hawks in Colorado. The utility pleaded guilty to six violations of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Eagle Protection Act. Under the settlement it agreed to pay $100,000 in fines and restitution to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” In Russia, a scientific workshop “Problems of bird electrocution and safety on overhead power lines of distribution voltage: modern scientific and practice experience” brought together ornithologists and engineers as well as representatives of the country’s environmental prosecutor’s office.

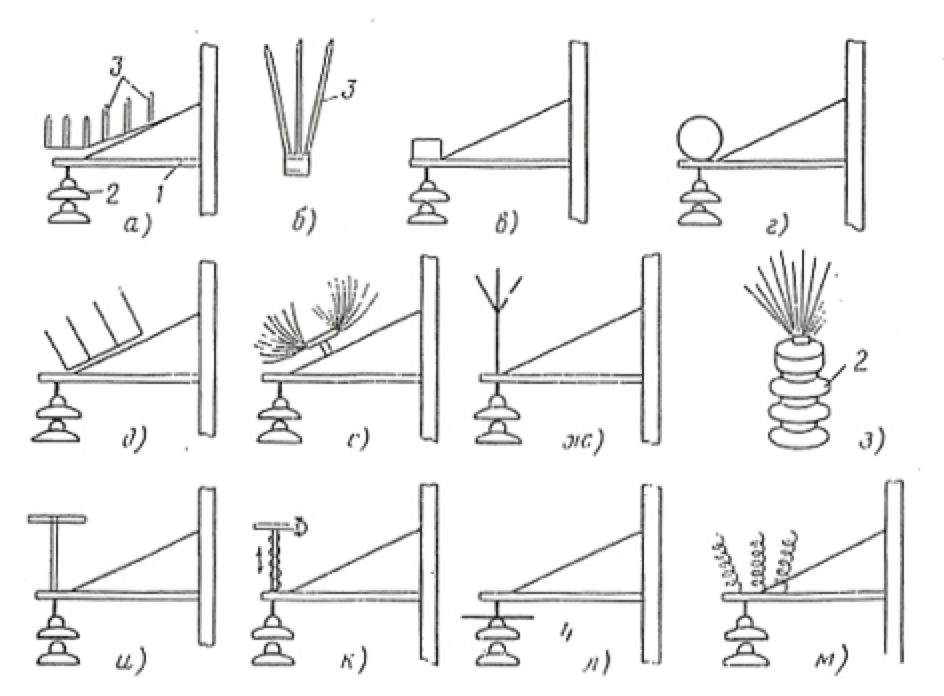

1. Preventing Outages Due to Roosting

The main device to prevent birds from roosting on a tower cross-arm is known as a perch guard (also known as bird discourager). Such perch management has been successfully applied in the U.S., Russia, Sweden, China, Germany and other countries to prevent problems due to bird streamers. Experience on one 400 kV line in South Africa, for example, demonstrated just how effective these can be in eliminating bird induced flashovers.

Perch guards are available on the market but must be dimensioned properly for each species, a factor that is extremely important for birds with long legs. To reduce cost and maximize effectiveness of this countermeasure, it is best to ensure collaboration between engineers and ornithologists to define the most suitable locations for each different type of tower. Care should also be taken to cover the complete area potentially occupied by birds, since they will quickly take over any space left open. Many utilities still use mostly metallic guards made of wire or rods, which could harm birds while landing. This argues in favor of flexible guards made of plastic. Again, as for distribution lines, these must be weather and UV-resistant, with some periodic maintenance cycle to monitor for signs of deterioration.

There are cases known where contamination to insulators is also due to other excretions apart from streamers, although these are typically less a risk due to lower conductivity. The solution here is to use a top insulator of larger diameter or install a protective plastic shield over it.

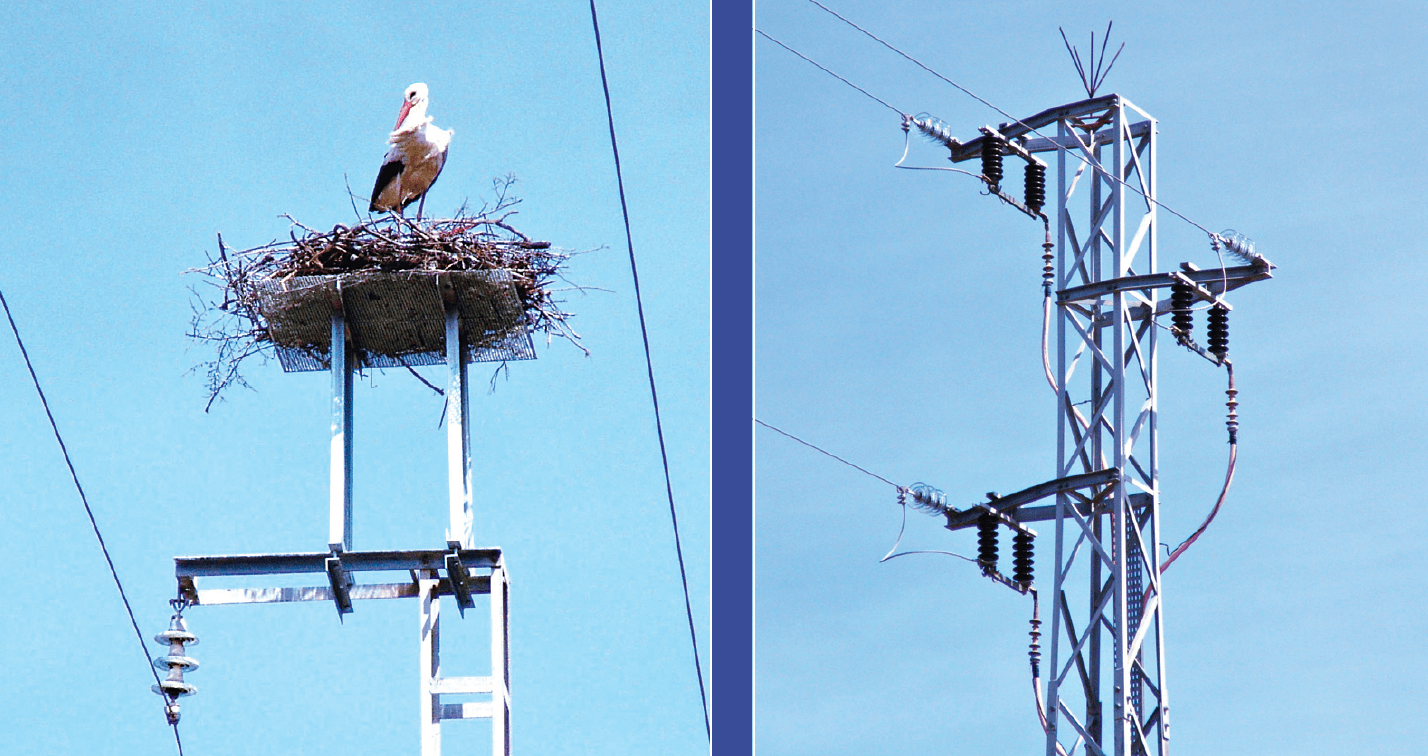

2. Preventing Outages Due to Nesting

Birds tend to conservative and try to build their nest on the same tower chosen the year before. There are anecdotes from a power utility that removed the nest of a white stork from the first tower entering a substation yet each time the stork returned to this same tower. After a ‘battle’ lasting 3 years, the substation was ‘bombarded’ by storks bringing branches and metal wire and the nest was left on the first tower as a sign of submission by the utility. (This is probably not entirely true, but the power company had to provide some explanation as to why the battle against the storks was lost).

Many power supply utilities worldwide report on how many nests have been taken down before birds return. This is not an easy task since the nest of a stork, for example, can measure 2 m in diameter and weigh up to 50 kg. To remove such a construction might take one or two linesmen a few hours. In fact, experience demonstrates that, if anything, removing nests is the incorrect approach.

This is because, during initial construction and subsequent re-construction, birds use branches and metal wire that can either fall causing an outage or expand downward from the nest, reducing the air gap and causing even more trouble. Therefore, if birds have already built their nest, it is better not to touch it before the birds vacate. Instead, the structure should, if anything, be protected by fence to keep out e.g. snakes, cats, which will be attracted to the nest. Snakes have been known to reach the top of even 400 kV transmission towers.

Once birds have raised their offspring and left the site, nests should be carefully re-located. In the long run, this would be the most successful and ‘bird-friendly’ approach, namely providing the birds with a nearby nesting alternative – usually some kind of pole with an installed platform and located near the existing nest site. Such alternative platforms should be built alongside the line and should be somewhat higher than the original nests to make them an attractive alternative. Then, once the nest has been re-located, the original tower should be equipped with bird guards to discourage future re-nesting. Again, to establish the best construction of alternative platforms, there should be close co-operation between line engineers and ornithologists.

Summary

Power companies should do whatever is possible to protect birds from overhead lines at distribution voltages and to protect overhead lines from birds at transmission voltages. At present there is a plenty of experience and proposals. However, these are not that well structured by specific bird species, which may be a key issue in their relative success or failure. To best solve the problem, there must be close collaboration between power engineers and ornithologists and the two should not regard each other as enemies.